(This post is cross-posted from a recent post on my blog and adapted for an audience already familiar with OpenStreetMap.)

A year ago, I was pretty sure I’d be spending all my free time mapping buildings and turn lanes. I did contribute plenty of them, but I also have a tendency to get distracted by ideas out of left field. During the past year, I wound up focusing on several kinds of features that never make it onto conventional maps. At some point, I took up mapping flags.

A taboo

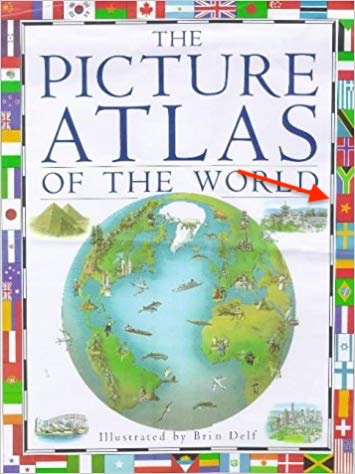

The first atlas I owned as a kid was The Picture Atlas of the World (Kemp & Delf). The beautifully illustrated maps and infographics endeared this volume to me for years, but it was the colorful ring of national flags around the front cover that made it irresistible to me at the bookstore. It’s a wonder that my parents gave in to my pleas and purchased this atlas, despite the “red flag” of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam gracing the cover. My grandparents fled the Communists in the ’50s, and they with my parents fled the Communists again in the ’70s. Like many refugees, they longed for Vietnam – especially after searching in vain for Vietnamese food – but hearing about life there today, good or bad, would often elicit dismissive eye-rolling about the Communists.

The flag of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam appears on the cover of this children’s illustrated atlas. (© Dorling Kindersley, used for critical commentary)

The flag of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam appears on the cover of this children’s illustrated atlas. (© Dorling Kindersley, used for critical commentary)

That was in a suburb of Cincinnati where Vietnamese are few and unknown. It was a bit easier for them to put the war behind them when no one around them seemed to know or care about Vietnam. But that wasn’t the case everywhere. Whenever we visited a Little Saigon in another city, I was fascinated by all the steps they had taken to maintain civic continuity with the old country: the major streets renamed “Sài Gòn” and “Trần Hưng Đạo”, the veterans marching in ARVN fatigues on holidays, the South Vietnamese flag raised proudly beside the American flag.

The City of Houston has renamed the major thoroughfares in its Little Saigon, posting Vietnamese signs of equal prominence as the older, more pronounceable English signs. Here, Wilcrest Drive has been renamed in honor of the unnamed soldiers of the Republic of Vietnam Military Forces (Chiến Sĩ Vô Danh VNCH). OpenStreetMap is the only online map that indicates the Vietnamese name, which is increasingly important for navigation as the English sign fades. (© Mapillary, CC BY-SA)

The City of Houston has renamed the major thoroughfares in its Little Saigon, posting Vietnamese signs of equal prominence as the older, more pronounceable English signs. Here, Wilcrest Drive has been renamed in honor of the unnamed soldiers of the Republic of Vietnam Military Forces (Chiến Sĩ Vô Danh VNCH). OpenStreetMap is the only online map that indicates the Vietnamese name, which is increasingly important for navigation as the English sign fades. (© Mapillary, CC BY-SA)

Later I’d learn that activists have convinced numerous city councils and state legislatures to give the South Vietnamese flag official status, regardless of international diplomacy, usually under a name like “Heritage and Freedom Flag”. The “yellow flag” is so important to these communities that, once in awhile, some official or business owner will unwittingly spark outrage, protests, and apologies by flying the wrong flag to represent the local Vietnamese American population.

The South Vietnamese flag flies at equal height with the American and California flags outside the offices of Người Việt, a Vietnamese-language newspaper. (© Codobai, CC BY-SA)

The South Vietnamese flag flies at equal height with the American and California flags outside the offices of Người Việt, a Vietnamese-language newspaper. (© Codobai, CC BY-SA)

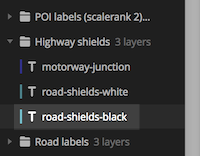

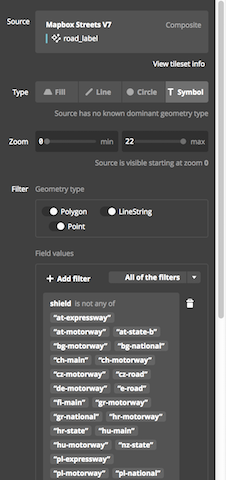

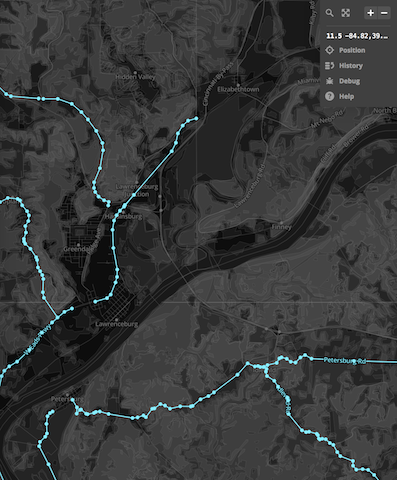

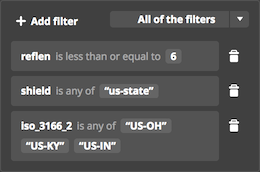

Name that flag

About six years ago, I noticed an approved scheme for mapping flagpoles and the flags that fly on them. According to the scheme, flags are classified as “national”, “regional”, “religious”, etc., and national flags are identified by ISO 3166 country code. It was specific enough to precisely describe most of the flags in my hometown, so I didn’t think much more of these tags after mapping a few American and state flags. I had more important things to contribute to OSM anyways, like redrawing roads that the Census Bureau had turned into abstract art.

The Vietnam War Memorial in Houston’s International District took over the middle of a shopping center parking lot. This being Texas, the flags are large enough to easily identify in aerial imagery. (© WhisperToMe, public domain)

The Vietnam War Memorial in Houston’s International District took over the middle of a shopping center parking lot. This being Texas, the flags are large enough to easily identify in aerial imagery. (© WhisperToMe, public domain)

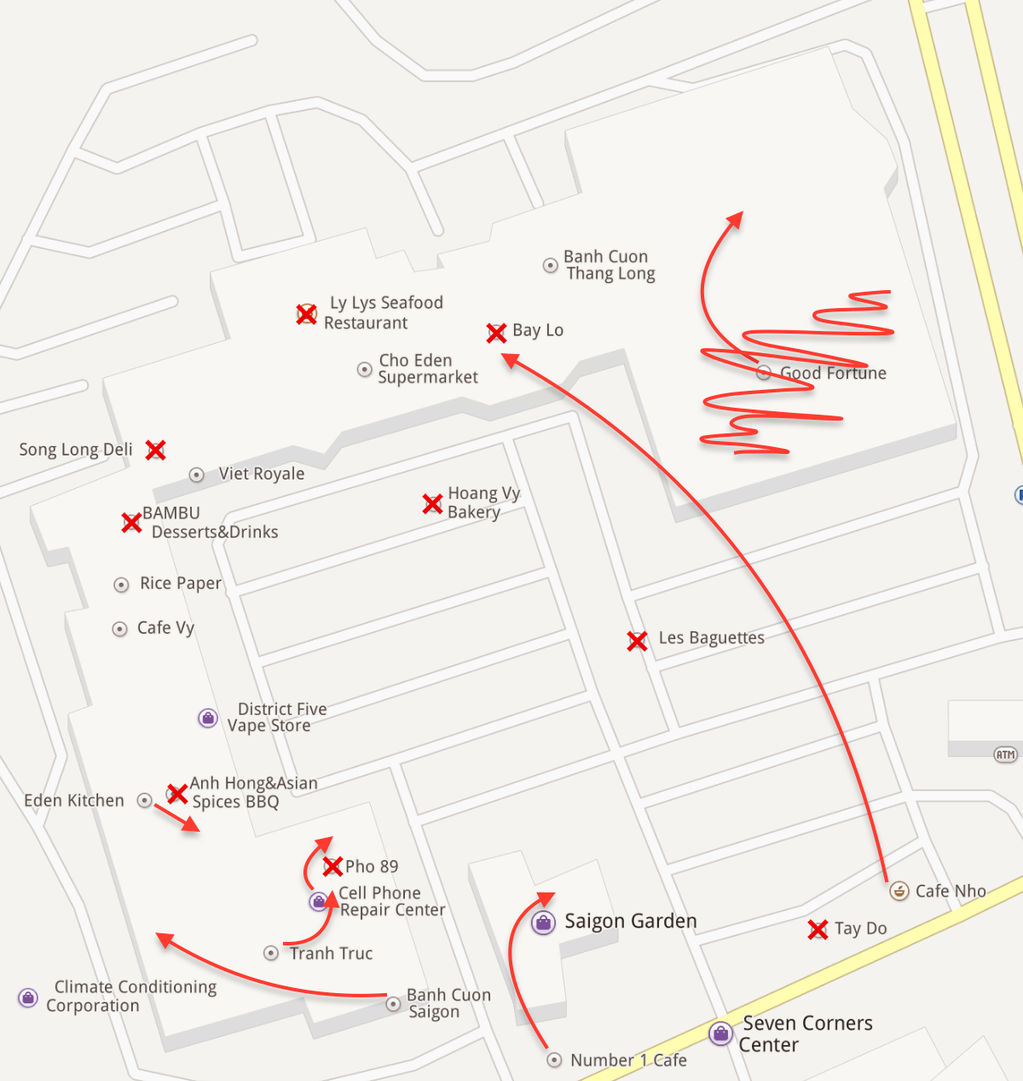

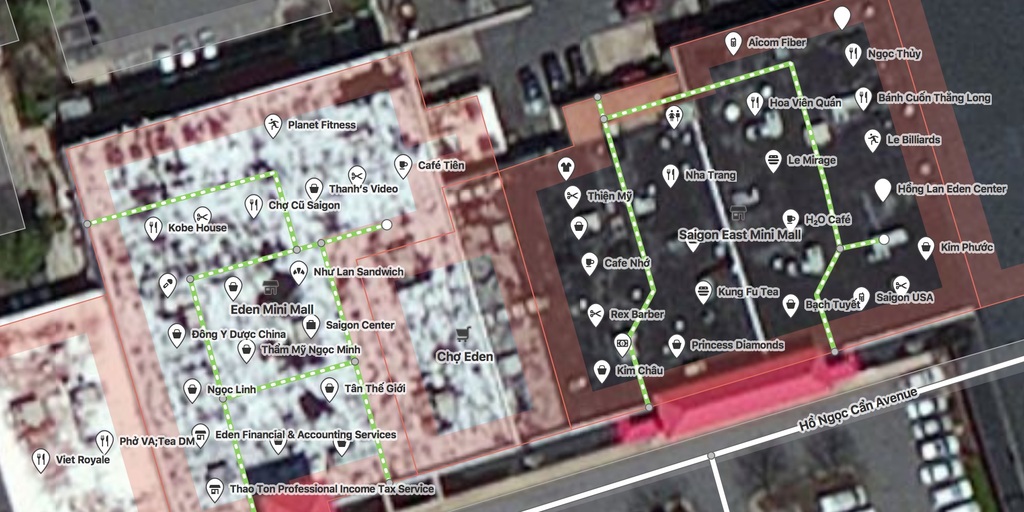

But then I started mapping Little Saigons. Nothing marks these communities as indelibly as the South Vietnamese flag. It’s the first thing to map, more important than the buildings and businesses. Yet no one has ever compiled a comprehensive listing of the places where the South Vietnamese flag flies. For that matter, no one has ever made a comprehensive map of these flags. That makes OSM the perfect place to start one.

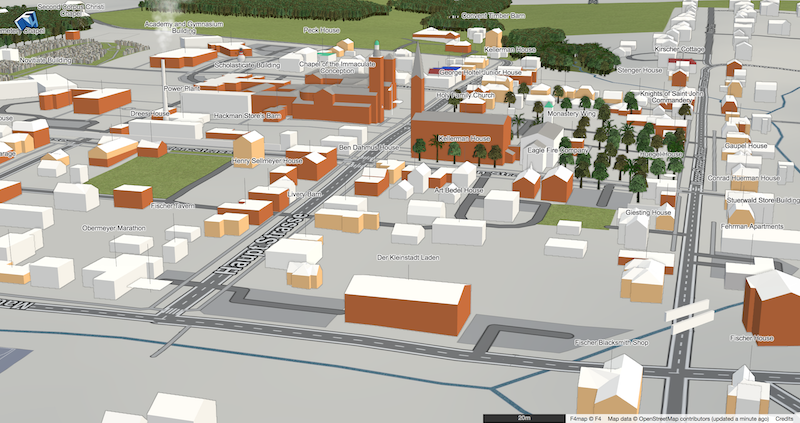

Unfortunately, when I started mapping South Vietnamese flags, the approved flag tags were too imprecise to identify it, because folks hadn’t considered that a flag could outlast its country. As it turns out, South Vietnam’s ISO country code was VN, but after the war, the ISO obsoleted North Vietnam’s VD and repurposed VN to represent the reunified Vietnam – one of the spoils of war, apparently. I couldn’t simply tag these flags as flag:type=national and country=VN, as the OSM Wiki suggested, without fearing that an OSM-powered map would automatically depict them as Communist flags in the heart of a fervently anticommunist community. Indeed, OSM2World would color the South Vietnamese flag red based on the ISO country code, though it is possible to override the color explicitly.

As far as I know so far, the only flag of Vietnam that flies outdoors in the U.S. on a permanent basis is the one outside the U.N. headquarters in New York. (© Kriss Omana, CC BY-SA)

As far as I know so far, the only flag of Vietnam that flies outdoors in the U.S. on a permanent basis is the one outside the U.N. headquarters in New York. (© Kriss Omana, CC BY-SA)

A quick search in taginfo showed me that someone had coined a more freeform flag:name key in 2014 and used it ad-hoc on a few flags without documenting the key on the wiki or campaigning to get it approved. flag:name=South Vietnam was an improvement in that I could make sure other mappers know which flag it is. But there was little chance that a future flag-bearing map renderer would special-case specific values of this key, given the sheer number of flag designs and the fact that the name could differ based on the local language where the flag flies. I needed to pair flag:name with another key set to an external identifier, which a renderer could use to look up machine-readable details in an external database.

I knew of two projects attempting to comprehensively catalog flag designs: Flags of the World and Wikidata. Both contain entries for the flag of South Vietnam, but I figured I’d eventually map other flags that weren’t in either database. My previous e-mail submissions to Flags of the World went nowhere, whereas anyone can create new Wikidata items while mapping. Moreover, Flags of the World lacks strictly unique identifiers: each webpage does have a somewhat memorable URL slug, but multiple flags can be documented on the same webpage. By contrast, Wikidata is organized around unique item identifiers (also called QIDs). It also has an API that makes it easy for software to reliably look up details, such as the flag’s aspect ratio, a scalable image to render, or even the Flags of the World URL slug if necessary.

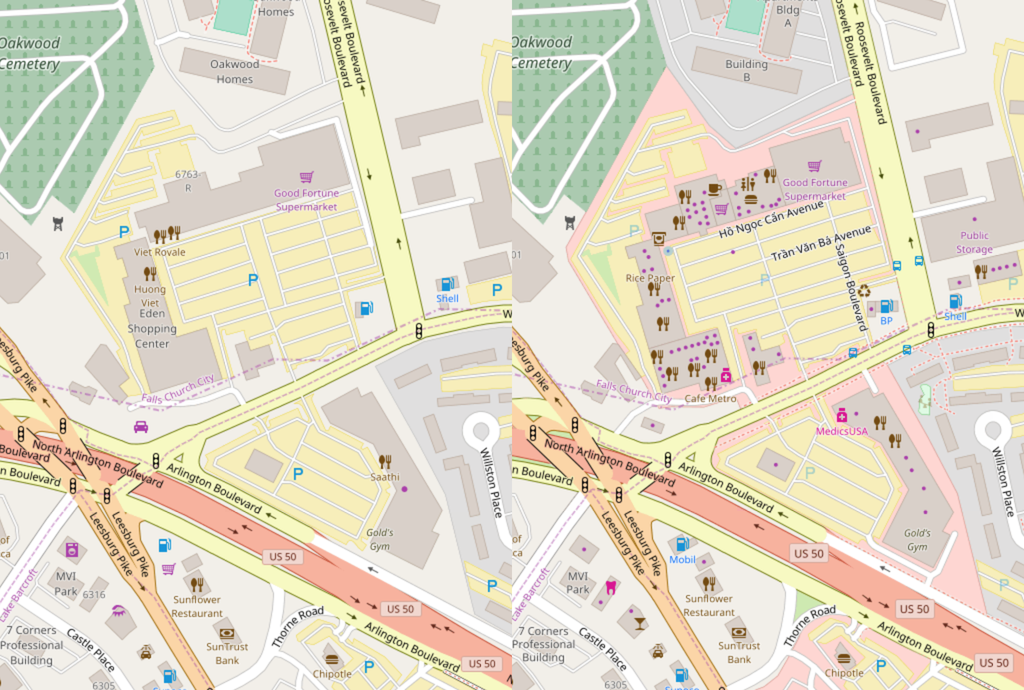

The Ohsome analysis tool shows

The Ohsome analysis tool shows flag:name was introduced in 2014 but went virtually unused until last year. flag:wikidata was introduced last year as well, and both keys have rapidly increased in usage. (© HeiGIT, map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, ODbL)

flag:wikidata follows the example of several other common keys that are set to QIDs, so I could use this key a bunch of times and expect other mappers and renderer developers to intuit the meaning behind it. But just in case, I informally suggested this new key on the man_made=flagpole tag’s talk page and eventually documented both flag:name and flag:wikidata on their own wiki pages to raise awareness.

Praying for a gentle breeze

Now I needed to get more flags on the map, to prove out the idea of tagging specific designs. I turned my attention back to my hometown and its mundane collection of American and state flags. Actually, I had missed plenty of other flags that needed QIDs for disambiguation: the five flags of the U.S. Armed Forces turned up at veterans’ memorials and outside the homes of many veterans. Some Catholic churches and cemeteries fly the local archdiocesan flag. McDonald’s restaurants fly a familiar Golden Arches flag. The high school I attended celebrates its Barcelonan exchange students with a Catalan flag – but my parents preferred to think of it as the similar-looking South Vietnamese flag.

St. Xavier High School in Cincinnati flies the flags of rival athletic teams, the three states where its students live, and the countries that send exchange students. Catalonia’s flag flies under the Spanish flag because of the school’s longstanding partnership with a school in Barcelona. (© Eugene Kim, CC BY)

St. Xavier High School in Cincinnati flies the flags of rival athletic teams, the three states where its students live, and the countries that send exchange students. Catalonia’s flag flies under the Spanish flag because of the school’s longstanding partnership with a school in Barcelona. (© Eugene Kim, CC BY)

Probably the main reason no one had ever rigorously catalogued individual South Vietnamese flags is that, important as each one may be to a particular community, it isn’t famous enough that word of that individual flag would usually spread across the country. Armchair mapping offers a way around that, since anyone can comfortably identify flags in street-level imagery and sometimes even aerial imagery. It took me only a few minutes to find South Vietnamese flags in the most well-known Little Saigon, in Garden Grove, California. But apart from that, it’s still time-consuming to think of Vietnamese shopping districts and scour imagery for a little yellow speck to zoom in on. Not nearly every Vietnamese grocery store would fly the South Vietnamese flag, just as not nearly every mainstream grocery store flies the American flag out front.

As a shortcut, I figured that places of worship catering to Vietnamese Americans would be just as likely to fly flags out front as mainstream places of worship, but much more likely to fly the South Vietnamese flag alongside the American flag. OSM has a lot of places of worship in the U.S., thanks to an import of the federal government’s official gazetteer, GNIS. GNIS is by no means comprehensive when it comes to places of worship, and it brought in lots of long-gone churches. Fortunately, it also has a tendency to call Vietnamese places of worship by descriptive names like “Vietnamese Alliance Church” rather than the actual, diacritic-laden names like “Hội Thánh Tin Lành Việt Nam”. So simply searching for “Vietnamese, United States” turned up quite a few churches, many of which do fly the South Vietnamese flag. I made sure to rename these churches according to signs I spotted in street-level imagery, and in some cases I had to move the church quite a distance from where GNIS had it, so there was a practical benefit in addition to the symbolism of getting flags on the map.

GNIS had this church as “Vietnamese Alliance Church”, but despite subsequent mass bot edits, it had never been tagged as belonging to the Christian and Missionary Alliance denomination. It also hadn’t been tagged with its equally prominent Vietnamese name, though many Protestant churches use the same Vietnamese name anyways. (© Märker Geospatial, CC BY-SA)

GNIS had this church as “Vietnamese Alliance Church”, but despite subsequent mass bot edits, it had never been tagged as belonging to the Christian and Missionary Alliance denomination. It also hadn’t been tagged with its equally prominent Vietnamese name, though many Protestant churches use the same Vietnamese name anyways. (© Märker Geospatial, CC BY-SA)

I turned up more Catholic churches by searching for the names that Vietnamese Catholics most commonly venerate, but in English: “Vietnamese Martyrs”, “Our Lady of Lavang”, “Andrew Dung Lac”. Aside from flags, these search results gave me a chance to micromap other details like outdoor Stations of the Cross. Similarly, I mapped a lot of statues after searching for Vietnamese words that commonly appear in the names of Buddhist temples, like “Phat” (Phật) and “Quang”.

The American, Holy See, and South Vietnamese flags fly outside Vietnamese Martyrs Catholic Church in Arlington, Texas. An outdoor Stations of the Cross is just out of view to the right. By sheer luck, this intersection sports a tornado siren – another hidden map feature I’ve been focusing on. (© Kevin Ewing, CC BY-SA)

The American, Holy See, and South Vietnamese flags fly outside Vietnamese Martyrs Catholic Church in Arlington, Texas. An outdoor Stations of the Cross is just out of view to the right. By sheer luck, this intersection sports a tornado siren – another hidden map feature I’ve been focusing on. (© Kevin Ewing, CC BY-SA)

I was pleasantly surprised to have access to street-level imagery in most of the localities where I found places of worship to map. That made it much easier to map unfurled flags. Sometimes, though, I had to resort to process of elimination. For example, sometimes the street-level imagery was taken at a time of day when the flags were down, but there was enough of a breeze to unfurl the flags in aerial imagery. From a set of three flags outside a Catholic church, I could often deduce that the one with a dark canton was the American flag, the yellow one was the South Vietnamese flag, and the yellow and white one was the flag of the Holy See. I made sure to tag any other flag I saw along the way, creating a corresponding Wikidata item if necessary.

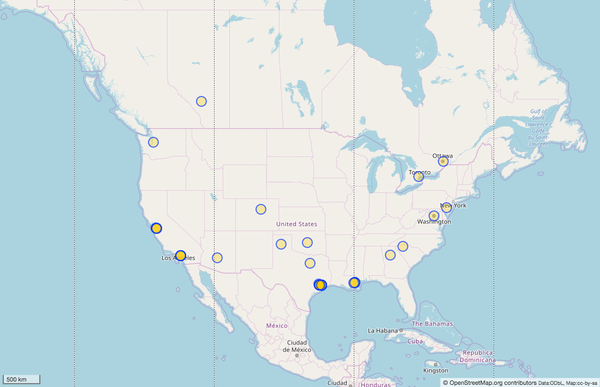

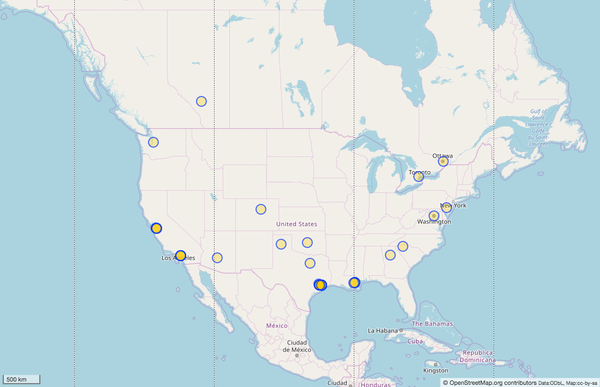

Ultimately, thanks in large part to Nominatim, I managed to map more than 45 South Vietnamese yellow flags across the U.S. and Canada, making it one of the most commonly tagged flag designs in OSM. (I did spot a couple red flags too, but notably none in the U.S. other than the one outside the U.N. headquarters in New York.) flag:wikidata is now one of the most commonly used Wikidata-related keys in OSM, more common than artist:wikidata and architect:wikidata, identifying Pride flags, Confederate flags, and everything in between.

(Run the query) It’s no surprise that Houston and Orange County in Southern California are so bedecked with yellow flags, given the very large Vietnamese populations in both areas. But they show up in some unexpected places too, like Greer, South Carolina, and Sundre, Alberta. OSM doesn’t record the stories behind these flags, but it could serve as a starting point for research. (© OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA; map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, ODbL)

(Run the query) It’s no surprise that Houston and Orange County in Southern California are so bedecked with yellow flags, given the very large Vietnamese populations in both areas. But they show up in some unexpected places too, like Greer, South Carolina, and Sundre, Alberta. OSM doesn’t record the stories behind these flags, but it could serve as a starting point for research. (© OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA; map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, ODbL)

I look forward to OSM’s coverage of flags increasing dramatically as others find out about this project and scour their own communities for flags. For now, only specialized 3D renderers show flags at all. overpass turbo let us see the invisible flag data, but it requires some training, such as in a walkthrough I gave at State of the Map U.S. last year. As flag coverage increases, I hope renderer developers will take note and add more sophisticated support for this data.

Raising the bar

I’m not mapping South Vietnamese flags in order to bear witness against Communism or to reopen old wounds. Rather, I want to ensure that Vietnamese American communities are represented on the map where they are today, in a way that’s meaningful to them. They already know where to find phở and bánh mì; what matters more is awareness and recognition. I want OSM’s attention to detail to bring people into the project from a broader range of backgrounds. The OSM community needs more diversity – not only among mappers and developers, but also among users and advocates – to establish the project’s relevance in society and keep it sustainable over the long term.

We need to expand our ideas of what OSM can excel at. Flag data is superfluous – until it represents new knowledge about the world that has never been expressed before or leads to improvements to the surrounding map. If we allow OSM to be judged solely by how well we provide the kind of information that people expect out of proprietary maps, OSM’s legacy will at best be a later, less efficient, less integrated Google Maps, merely a more current, detailed imitation of the paper maps in my collection. To be sure, roads, buildings, and businesses are an important baseline for a layperson’s trust in a map, but a baseline alone doesn’t capture people’s imaginations and spur them to action. Let OSM’s corporate infantry figure out how the project can compete with proprietary data sets on baseline data, while we grassroots mappers focus on mapping something quirkier, something more colorful that gets the next generation hooked on maps.

You can help

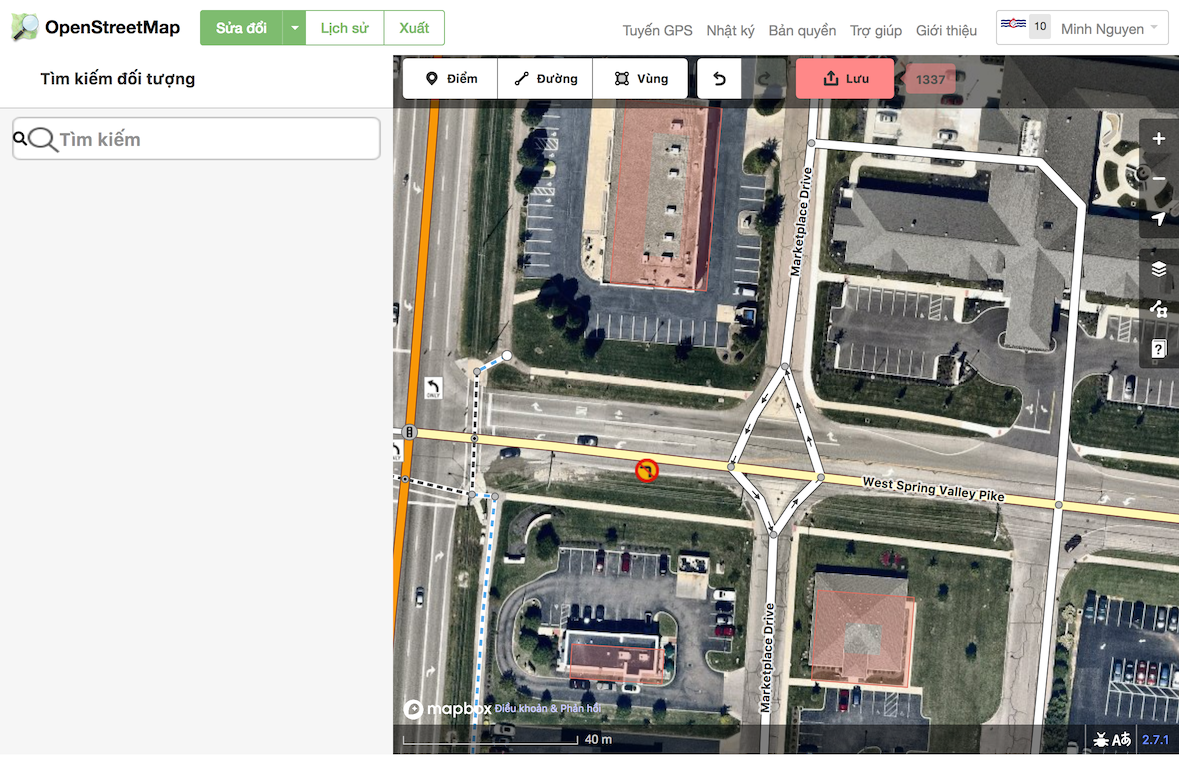

To map a flagpole in iD, add a Point and search the feature types for flagpole in the sidebar. The built-in fields so far only let you indicate the flag’s type (flag:type) and ISO country code (country), but you can add the flag:name and flag:wikidata keys manually in the “All tags” section at the bottom of the sidebar. The wiki’s flagpole documentation explains some of the nuances, like the difference between governmental and organisation, and how to find or create a QID in Wikidata. But don’t stop there: think creatively about what else might be important to a community’s identity and find ways to represent that on the map too.

Location:

The flag of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam appears on the cover of this children’s illustrated atlas. (© Dorling Kindersley, used for critical commentary)

The flag of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam appears on the cover of this children’s illustrated atlas. (© Dorling Kindersley, used for critical commentary)

Look sideways: these pumpkins at Wendel Farms were previously visible in Bing and other aerial imagery, but the ways clearly need to be deleted now that the pumpkin design has been cut down (and replaced).

Look sideways: these pumpkins at Wendel Farms were previously visible in Bing and other aerial imagery, but the ways clearly need to be deleted now that the pumpkin design has been cut down (and replaced).